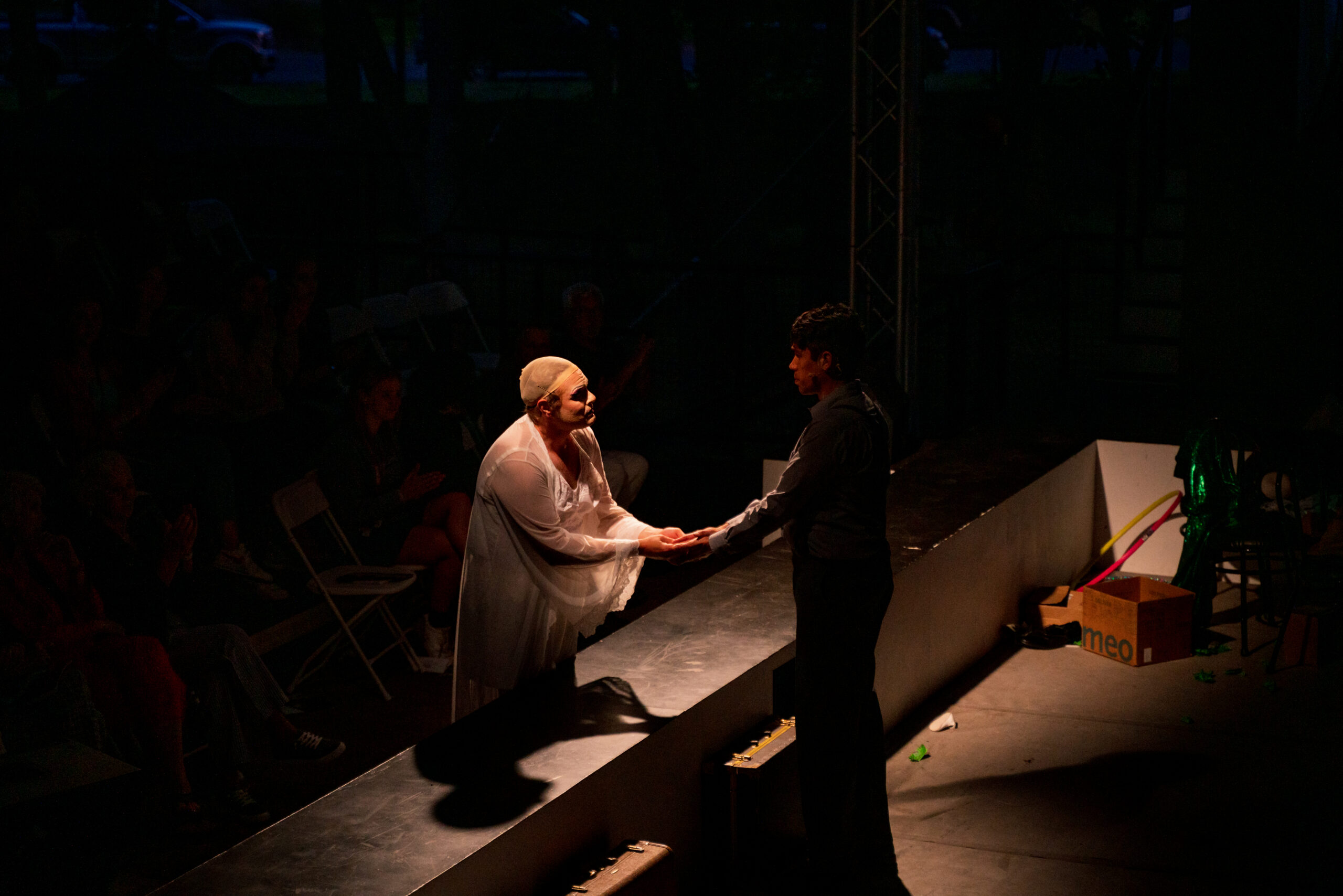

Cabaret

Music Direction by Rick Church

Choreographed by Jennifer Lott

Set Designer: Jacob Sikorski

Lighting Designer: Alexandra Casillas

Costume Designer: Caroline Frias

Props Designer: Alex Kaplan

Sound Designer: Jake Neighbors

Makeup Artist: Brandon Shafer

Featuring: Jonathan Allsop, Ben Carroll, JT Langlas, Daniel Lendzian, Katharine Mangold, Paris Manzanares, Michael Norton, Minda Nyquist, Rocheny Princien, Asia Pyron, Sawyer Reynolds, Grace Zucco

Notes from POV: Cabaret is the story of a queer space that existed in Berlin in the 1920s and 30s. Famous with Europeans, the erotic metropolis of Berlin became a sex-tourist destination for those seeking liberation from upper-middle-class societal constraints. Prostitution proliferated. Sexual mores adjusted, irised open and blossomed. And, most notably, night clubs sprouted. These venues in Weimar Germany were a rare addition to a handful of moments historically when queer values could exist in a space safely. Many clubs– and the performances set within– held space for those not only seeking sexual liberation but also for ‘others’ in a culture to celebrate their otherness and provoke the cis-normative culture, interrogating normative values of monogomy, heteronormativity, class and race.

As we know, ultimately, in 1933, this provocation emerging in the cultural corners and alleyways of Weimar Berlin was perceived as taunting and hit a boiling point. It was seen by those outside the community as a condescending, classed performance of privilege, and an intellectually fearful, populist, clear valued political system overtook this space, murdered its participants, erased its values, and set the community back half a century.

In the 1930s, Christopher Isherwood, a Londoner whose “brilliant sketches of a society in decay” in The Berlin Stories and Goodbye to Berlin couldn’t write openly about his own homosexuality. In truth, he came to Berlin with his friend W.H. Auden, to seek a safe space for physical fulfillment with men. Twenty years after Isherwood’s Berlin adventures, the original production of Cabaret depicts him as a heterosexual forming a romantic relationship with nightclub singer Sally Bowles. In real life there had, of course, been no such affair and rather, Isherwood explained there had been a real Sally Bowles, a young Englishwoman in Berlin called Jean Ross. As Isherwood recalled much later: “Berlin meant boys.” Revival after revival over time seeks to undo that one vital erasure by increments. This production will live in the following truth: Cliff travels to Berlin and finds the beginning of his coming out story in the warm, sparkling embrace of Weimar’s Berlin’s cabaret culture. In it he finds cover in his life long friend, Sally, and chosen family in Fraulein Schneider and Herr Shultz. But when the enemy penetrates the safe space, Cliff retreats to a hetero-normative path. When the enemy attacks, he flees rather than fights for his safe space.

Foundationally, this production, like all productions prior, aims to shed a sharp light on the undercurrents in our own country that mirror that of pre-nazi Germany. It is vitally important to look at the ways in which we, too, can avoid the humanitarian fate that destroyed western society in the last century. Hal Prince was intentional in this aim. His original objective in developing this piece was to expose the audiences to the brutal truth that what happened in Germany could happen here. Famously, the ending of the original show was going to showcase a film of the march on Selma. While Prince ultimately did not include the film, the production remained intentional in the playing out of this metaphor; their rehearsals focused on drawing a comparison from the socio-political energy of Weimar Berlin to 1967’s America.

We honor Prince’s intention to use this story as a springboard to warn folks that Things are Not Ok. We do not live in a friendly, moderate land of polite discourse. Populism is to be feared. If Prince was scared about this in 1967, we should all be doubly scared now. Our safe spaces are in danger.

AND, somehow as frightening as all the capital riots and deep state tik toks combined, the final and additional truth that sits on top of the primal and consistent fear of repeated history is the thing that keeps me up at night. Let’s say the devil does come at us in some horrifyingly mirrored manner to the genocide that occurred in the last century (likely). Let’s say this production, like all those that came before, powerfully reminds us it could happen today (hopefully). The question that remains: what if how we react to the devil has as much impact as the devil himself? In getting through the vortex of conditions we live in, how have our survival mechanisms stopped serving us?

Cliff’s retreat to a hetero-normative path for a few weeks before he flees Nazi Germany is a small concession compared to the overwhelming death and torture that developed around him. As a team, we aren’t here to punish Cliff, nor is it useful to punish ourselves. (Caveat: The EMCEE *does* enjoy a good spanking.) Cliff’s survival response is a completely understandable and efficacious action defending himself from a political and populist thought-system that was seeking to intentionally annihilate him and his kind. And yet, our production proposes that there were consequences to his retreat. In service of breaking this story out into metaphor, the way we are determined to do, we need Cliff to bear witness to his own small contributions before he’s allowed the relief and transcendence we all deserve. Before Cliff passes, he must must fully witness what happens to his friends after he has the privilege of retreating and fleeing. The play will end with the cabaret performers rounded up and killed in a gas chamber, as in the 1998 Mendes adaptation, this time with pink triangles attached to what’s left of their clothing. Without adornment, they go back to the world naked as they came. And Cliff gets to pass on.

“And that I did not give to anyone the responsibility for my life. It is mine. I made it. And can do what I want to with it. Give it back, someday, without bitterness, to the wild and weedy dunes.”- Mary Oliver